21/10/2016

The latter part of our most recent auction contained an intriguing collection of lace, baby clothes and ceremonial trains which were carefully packed into boxes and stored in the attic of West Horsley Place, an Elizabethan manor house. These treasures were passed down and added to by generations of some of the richest or most influential women of their day. The textiles chart the extraordinary lives of these women, who provided wealth in exchange for coronets and status but found love in the process, others who guided and influenced their husband's career and one whose relationship ended in scandal and divorce.

The story begins with Juliana Cohen (1831-1877), who married her cousin the Baron Mayer Amschel de Rothschild (1818-1874) in 1850. He was from the British branch of the wealthy Rothschild dynasty. Known to his friends as ‘Muffy’, he never played an active role in the banking business, instead indulging in more ‘gentlemanly’ pursuits.

His built the palatial Mentmore Towers, Buckinghamshire (see below) between 1852 and 1854 to house his important art collection. He required a country estate within close proximity of London and it was one of the greatest houses to be built in the Victorian era. He bred race horses, was a member of the jockey club and was an accomplished rider despite his substantial frame.

Many of the metal trunks which held the lace and textiles and some of the embroidered handkerchiefs bear the name of his sister-in-law 'Miss Cohen’, who died a spinster in 1906. She was obviously a keen collector and often made gifts of special pieces to her female relations, as little notes attest, and presumably upon her death to her niece Hannah.

The Rothschilds had just one child, a daughter called Hannah (1851-1890). As an only child she was pampered and protected from the outside world, largely brought up within the vast 100-room Mentmore Towers, surrounded by priceless art. She was not noted for her beauty but for her immense wealth. In 1874 her father died and aged just 23 she inherited his father’s vast fortune, which included Mentmore, its famed art collection, millions of pounds and vast tracts of North America. She became the richest woman in Britain and a highly eligible heiress.

Left: Juliana Rothschild with her daughter Hannah inside Mentmore’s great hall

Right: Hannah de Rothschild

She was introduced to the handsome, dashing Archibald, Earl of Rosebery (1847-1929) at the races by their neighbour and then Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. She quickly fell for Archibald’s charms. At the time Rosebery was as popular a figure as members of the Royal family. However, Hannah was Jewish and this posed a problem in those less enlightened times. To marry into the British aristocracy was highly controversial. Queen Victoria was known to feel it improper to raise a Jew to the peerage and the Prince of Wales, Edward was advised not to attend Rothschild social events though he did so privately.

The Rothschilds too were not keen on the match, preferring their offspring to marry cousins to keep the wealth within the family but also within the faith.

Archibald Primrose was intelligent, handsome, cultivated and wealthy in his own right with huge estates in Scotland and England (although this was nothing in comparison to Hannah). He was such a catch that ultimately the Rothschild family came round to the idea and after a brief engagement of a few months, their marriage took place in June 1874. Benjamin Disraeli and the Prince of Wales were guests of honour.

It was a happy marriage and Hannah became an influential political hostess, helping to steer her husband’s career. She immersed herself in philanthropic and charitable works. There are dozens of her monogrammed handkerchiefs (lots 467 and 468) with beautiful whitework cyphers edged in precious lace – obviously nothing was too good for the richest woman in England!

Hannah died in 1890 aged just 39 and Lord Rosebery was devastated by her loss. After Gladstone’s death in 1894 he became Prime Minsister but his beloved Hannah never lived to see it. Their marriage produced four children: Lady Sybil (born in 1879), Lady Margaret, who was known as Peggy (1881), Harry, Lord Dalmeny (1882) and Neil (1882).

Lady Margaret (Peggy) Marchioness of Crewe in 1909

Their daughters Lady Peggy and Lady Sybil were both favourites of Queen Victoria. Peggy was attractive, intelligent and witty. In 1899 she married a close friend of her father, the 1st and last Marquess of Crewe, Robert Crewe-Milnes. She was just 18 and he 41. He was a widower with three daughters; his son and heir Richard had tragically died as a child. His eldest daughter Annabel was just 5 months younger than Peggy!

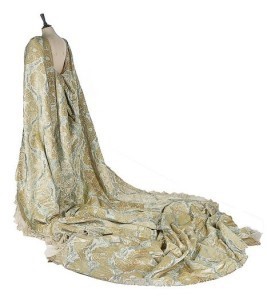

The wedding took place in Westminster Abbey with ten bridesmaids and over 600 guests. It is possible that the ice-blue and ivory voided velvet train, probably by Worth (lot 477, see below), was worn by her.

Like her mother before her, she came to the fore as a political hostess and helped her husband in his political work. Lace collecting became a favourite pastime and a notebook (lot 476, see below) shows the meticulous listing of her lace collection in 1910.

Peggy and Robert had two children: Richard, the son and heir, who died when he was just 11, and Lady Mary, who was born in 1915. Lot 455 probably relates to Lady Mary and her brother. King George V was Mary's godfather. Some of the baby robes in lots 456 to 458 may have belonged to some of the other Crewe-Milne children.

Lady Mary in 1935, aged 19, wearing her Cartier engagement ring

Lady Mary in 1935, aged 19, wearing her Cartier engagement ring

Lady Mary was a notable beauty and an extremely eligible heiress. In 1935, at the age of 19, she married George Innes-Ker, the 9th Duke of Roxburghe (known as Bobo to his friends).

The wedding of Lady Mary and George, 9th Duke of Roxburghe

The wedding of Lady Mary and George, 9th Duke of Roxburghe

George and Mary were married at Westminster Abbey and the ceremony was broadcast in newsreels in cinemas across the land. They made their home in his 100-room Ducal seat, Floors Castle, near Kelso in Scotland, which had been lavishly decorated by his American mother, who had been one of the ‘Dollar Princesses’.

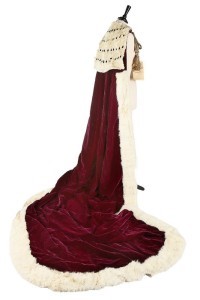

Mary, with her dark, good looks, was chosen to carry the Queen’s train at the coronation of King George VI in 1937. The crimson velvet and fur-trimmed train, part of the coronation robes, was probably hers (lot 477, see below) as are handkerchiefs bearing her monogram, lot 468.

Mary and George spent many happy years together, travelling to India and Egypt during the war. But after eighteen childless years of marriage, the Duke needed an heir. The request for Mary to quit Floors Castle was delivered via the butler on a silver tray. She refused to be evicted and barricaded herself into the castle for six weeks, during which time the Duke cut off the electricity, telephone and gas. He tried to cut off the water too but was persuaded to relent. In 1953 a divorce settlement was finally reached. The Duke quickly re-married in 1954 and the much-longed-for male heir was provided later the same year. When Lady Mary’s mother Peggy (Marchioness of Crewe) died in 1967, she left her the Tudor red brick house, West Horsley Place. Upon Mary's death in 2014 she in turn bequeathed it to her nephew, the celebrated broadcaster Bamber Gascoigne. This collection of lace and textiles was discovered in the dilapidated attics of the house. The money raised will be used to help restore the house and set up an opera in the estate grounds. As a lifelong supporter and patron of the arts it is likely that Lady Mary would have approved!